Europe is facing a demographic winter. As birth rates plummet across the continent, everyone is looking for answers. A common, popular narrative is very popular: the crisis is a result of shifting values.

The argument is simple. We have become too individualistic. If we could just revive the traditional belief that having children is a “duty to society”, rather than a mere lifestyle choice, birth rates would naturally recover.

It is a hypothesis that places culture upstream of economics. But is it true?

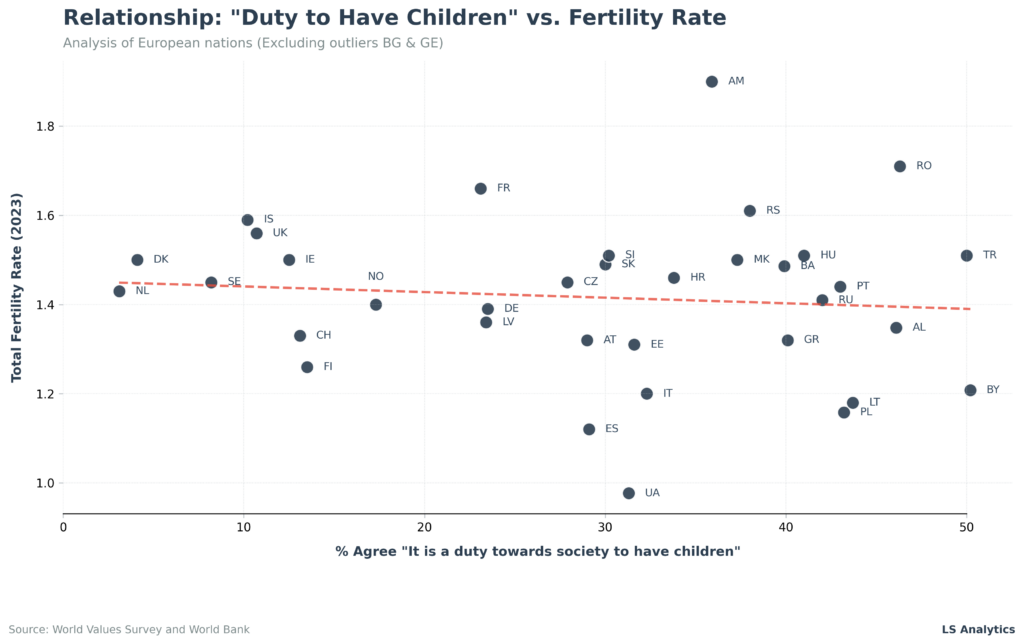

We tested this theory by correlating cultural data from the World Values Survey (WVS) with the most recent fertility ratios.

The Hypothesis: Duty = Fertility?

To measure social values, we looked at the percentage of respondents in European nations who agreed with the statement: “It is a duty towards society to have children.” The data is obtained from the World Values Survey and has been very popular on social media recently. We then mapped this against the fertility ratios.

If the “values” argument were correct, we would expect to see a clear upward trend. Countries with a high sense of social obligation should have significantly higher fertility rates.

The Illusion of Correlation

At first glance, the data provides a hint of promise for the traditionalists.

When we plot all countries, we see a weak correlation. It is a weak positive signal, but it is there. The trend line slopes gently upward, suggesting that social pressure may have a small effect on the decision to have children.

But a closer look reveals that this trend relies almost entirely on two particular data points.

The “Bulgaria Effect”

In the top-right corner of the chart, two nations sit far apart from the rest of Europe: Bulgaria and Georgia.

- Bulgaria: 82.7% of people view childbearing as a duty. TFR: 1.81.

- Georgia: 73.7% of people view childbearing as a duty. TFR: 1.81.

These two countries are outliers. They combine extreme adherence to traditional values with fertility rates significantly higher than the European average (though still below the replacement level of 2.1).

Because they are so extreme, they act like a magnet, pulling the entire trend line upwards. They create the appearance of a correlation that does not exist in the rest of the continent.

Values are not related to TFR

To understand the true relationship between values and fertility throughout the vast majority of Europe, we reran the analysis, this time excluding Bulgaria and Georgia.

The result is clear.

Without the two countries, the correlation vanishes. The trend line flattens out completely.

Once you remove the two outliers, the relationship between “duty” and “fertility” drops to virtually zero or even a negative one. For the remaining countries, from Portugal to Poland, from Sweden to Spain, knowing how much a population values the duty of parenthood tells us absolutely nothing about their birth rates.

In fact, the data reveal a paradox that directly contradicts the “duty” narrative.

Take the Netherlands. Only 3% of Dutch citizens agree that having children is a social duty. To the Dutch, parenting is strictly a personal choice. Yet, their fertility rate (1.43) is not the lowest one.

Compare this to Poland, where 43% of the population believes in the duty to bear children. Despite exerting 14 times more social pressure than the Netherlands, Poland’s fertility rate has collapsed to 1.16, one of the lowest in Europe.

This pattern holds across the continent. The Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, and Denmark) maintain fertility rates that outperform those of many of their more traditional Southern and Eastern European neighbours.

Conclusion

The data suggest that “guilt” is not a viable demographic strategy.

The countries with slightly higher fertility rates aren’t the ones that value parenthood the most.

For decision-makers, the lesson is clear. If you want to fix the demographic crisis, we can’t just look at values surveys; we need to consider economic barriers. The “duty” lever is disconnected from the European reality.